We’ve talked in some earlier posts about the cutbacks at The Times-Picayune (TP) in New Orleans, the local reaction, and what it may mean for the publishing industry and the future of news reporting as a whole. While this week’s news that the TP’s award-winning Katrina reporter Mark Schleifstein is staying with the paper after the restructuring is encouraging, the paper’s fate still remains unchanged (despite strong local opposition), prompting criticism and gloomy predictions of the state of journalism in general.

As Charles P. Pierce wrote in Esquire back in May, when the news of the TP cutbacks broke:

The main reason that newspapers are failing in this country is that they are being set up to fail by publishers who think like hedge fund cowboys, and by editors who think like corporate officers. If there’s another major institution in this country that hasn’t yet gone out of its way to fail the people of New Orleans, I don’t know what it is.

Errol Laborde, editor in chief of Renaissance Publishing and editor/associate publisher of New Orleans Magazine, expressed the frustration many New Orleanians had been feeling on the Editor’s Room blog on MyNewOrleans.com, when he relayed the simple fact that the day after the Saints will play the Green Bay Packers the TP won’t be publishing (Monday, October 1, 2012). Laborde writes:

As of that day, the Saints will be in the only major league market without a daily newspaper. […]

What the Newhouses hope is that on that day New Orleans sports fans will rush to their iThings and read about the game online. What they are overlooking is that there will be many other web-based options, including TV sites (which will have the advantage of professional video), for the fans to go to. The geniuses in Jersey will have transformed what was once the prime local news source into another app button to push…

Perhaps sports fans needn’t worry as much as the readers who want to keep up with the coverage of local politics, schools, and any other social issues.

In her excellent July 20 article for Columbia Journalism Review, “How to worry about a clicks-driven Times-Picayune,” a former education reporter for the paper Sarah Carr asks: “If clicks drove coverage at The Times-Picayune in New Orleans — a more realistic prospect than it’s ever been — what kind of publication would we get?”

Carr says she has no plans to stay with the paper after its redesign under NOLA Media Group kicks in, but she does say she worries “what the changes could mean for the newspaper, the community, and my talented colleagues, particularly if pageviews drive coverage and compensation to a significant extent.”

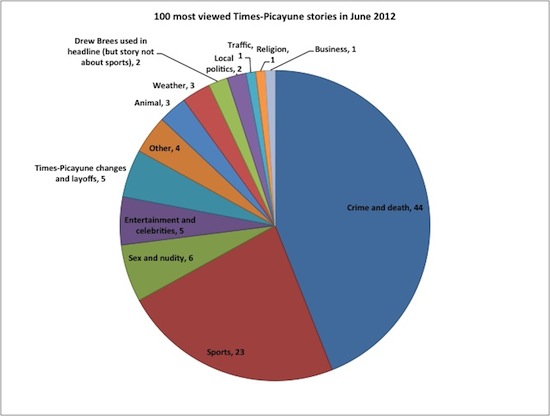

Together with TP’s online editor Cathy Hughes, Carr compiled and analyzed data for the stories that have received most pageviews (see chart below for the June 2012 data).

The results, Carr says, have her worried:

In a doomsday scenario, we would read only about sex, sports, crime, and more crime. […]

The 100 most popular stories that month included no coverage of education, health, immigration, or housing. Less than 10 percent of the stories were even tangentially related to social or public policy. Only two addressed a serious political debate (and one of the two probably made the list simply because Drew Brees was mentioned in the headline). But the stories documented murder, mayhem, and mischief in abundance. As a chronicle of human cruelty and misfortune, the list was nothing short of sublime.

The tabloids have exploited our lust for the sensational and the depraved for centuries, of course, nothing new there. However, what’s troubling in this scenario, Carr points out, is that local, community-based newspapers “have historically taken a different, and more paternalistic, approach. They have always covered their fair share of sports, crime, and fluff, but they include vegetables in addition to dessert, aiming for the balanced meal.”

And while NOLA Media Group hasn’t explicitly stated whether it will focus on the clicks-driven coverage, the mere fact that, according to Carr, the company “left the sports and entertainment departments comparatively intact” while other departments have suffered drastic cutbacks, points to where its priorities are.

Carr says she has two major concerns in particular after viewing the traffic data. The first one is that the clicks-driven coverage would only cover “societal extremes.” She writes:

First, if existing click patterns drove coverage, the newspaper would write almost exclusively about the dead, the dying, and the overpaid. New Orleanians would read about two tiny, polarized slivers of society: The fantastically wealthy and privileged sports stars and celebrities (particularly the white celebrities); and the fantastically violent criminals and their unfortunate victims (particularly the white victims). As they did in June, the big sports and crime stories almost always generate the most clicks. Stories about education, healthcare, and the overwhelmingly majority of poor people who do not kill anyone receive comparatively few. […]

We would know all there is to know about Drew Brees’s contract and the most sensational of the city’s homicides, but much less about everything else.

Carr’s second concern with the local clicks-driven journalism is its potential impact on specific beats like education, mainly because some aspects of it get more attention (and clicks) than others. She says:

If clicks drove coverage on the education beat, not only would reporters write less about the city schools, they would focus disproportionately on what I would describe as micro-feuds — intense, bitter, and divisive issues that are relevant only to a small fraction of society.

Carr’s main point seems to be: Yes, we’re driven to the sensational journalism due to our (human) nature, as well as the news that might directly affect us, but that shouldn’t be the focal point of a local community paper. Instead, its function is to help us “understand the more subtle and important ways in which policy connects to our daily lives.” Which doesn’t always fall under the news coverage that will get the most clicks.

Image of Brenda Starr is by Mike Licht, NotionsCapital.com, used under its Creative Commons license.