With Encyclopedia Britannica‘s March 13 announcement that it’s shutting down production of its print edition and is going digital, trying to explain to today’s kids the selling-door-to-door concept has become even more fun. And while Roger Angell waxes nostalgic at The New Yorker, noting that the news came as a “dull shock,” Megan McArdle, senior editor at The Atlantic, quips, “Wikipedia rules! Britannica drools! Ahem.”

Whether you like it or not, as Rene Lynch points out in Chicago Tribune, “The move may be the single most powerful symbol to date of our rapidly changing media world, a world in which hard copies of books could become a quaint thing of the past.”

We have mentioned in last week’s post, “Demand Media: Down, Not Dead,” that content farms, as witnessed by the trials and tribulations of the once-thriving Demand Media, don’t have what powerful media outlets have: brand and brand loyalty. That’s why it would be interesting to see how the digital version of the Encyclopedia Britannica does. After 244 years in print, one would imagine the Britannica has built some of that loyalty.

Sure, the merits of churning out the 30-plus-volume, pricy “leather-bound behemoth” on a yearly basis and skimming the surface on the competing Wikipedia could both be disputed — after all, there are bound to be inaccuracies in both encyclopedias. Quality of content matters, but so does delivery, and both are tied to your brand and how you capitalize on it.

We’ve referenced Megan Garber’s recent article in The Atlantic, “The New York Times, the Content Farm, and the Power of the Brand,” where she mentions that, “while digital revenues are down overall, digital revenues at the Times and other core properties — isolated out from the company’s other holdings — actually grew by 10 percent between 2010 and 2011.”

Garber mentions how respectable media outlets such as The New York Times, the International Herald Tribune, and The Boston Globe are actually doing OK, considering. She also slams content farms, saying that:

Content farms and their products are, essentially, words without brands. They float, aimlessly, in the ether, waiting and hoping for just the right search query to make them, suddenly, relevant. They operate in the fickle world of eyeballs and clicks. They cling, because they must, to the whim and whimsy of human curiosity.

What media businesses have (and content farms don’t) are that they are hosts and the brands in and by themselves. “The Times has a recognition and a loyalty and a cultural relevance and a social significance that both transcend and amplify the content it produces,” Garber says. “It is anchored not to Google, but to itself…”

According to Garber, that gives these entities the “power to convert loyal readers into subscribers, and to pitch those subscribers to advertisers.” They only need to find successful ways to commercialize on their brands, Garber notes, preferably without tarnishing their reputation in the process.

Erik Kain, contributing writer at Forbes, also references Garber’s article, pointing out that:

These aren’t just wise words for media companies navigating the dangerous digital straits of our time. Basically anyone who has a presence online these days is building a brand. Originality, sincerity, and quality are much more important than making sure you get the right SEO tricks down — though certainly when it comes to clicks from random eyeballs, those things matter as well.

It ties nicely, he says, with the “the emergence of a more social web” — where media outlets, big and small, can take advantage of “an entirely more social online experience.”

Kain’s opinion is backed by some numbers. A Facebook-sponsored study, conducted by Forrester Consulting late last year, found that “76 percent of marketing professionals surveyed agreed that social media is important for brand building and 72 percent agreed that it is important for customer loyalty.”

Kain says:

In the social environment the web is becoming people cultivate images, videos, and ideas and let good content swirl up and ferment across the fields of Pinterest, Facebook, and various other outlets.

We’re not just searching anymore. We’re following and sharing and carrying on conversations. We’re exploring one another and the weird things we all like. Eventually the whole concept of searching and then scrolling through the top ten hits on Google will die out. We’ll stop asking a search engine to guess because we’ll have so many other ways to find what we’re looking for.

Google, I think, understands this. Hence the change that Megan [Garber] mentions, away from SEO tricks and toward good, original content.

Speaking of SEO tricks, at SXWS last week, Google’s Matt Cutts discussed how Google is planning to cut down on “over-optimized” (for SEO) sites. And while there’s some confusion regarding what Google defines as over-optimized and just how it will “punish” those sites, the prevalent public opinion could be perhaps summarized by Barbara Hudson’s comment in her article for E-Commerce Times: “Most of us refer to them as ‘search spam’; when those sites are gone, nothing of value will be lost.”

Whatever Google has up its sleeve, we will find out soon. Garber reminds us that no matter what direction online media business is taking, and how it makes money these days, brand is key. She says:

Your community is part of your brand. In a very real sense, it is your brand. Content, floating in the ether, risks matching its attitude to its worth: easy, yes, but also free.

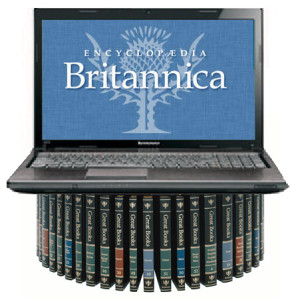

Image by Mike Licht, NotionsCapital.com, used under its Creative Commons license.