When you reason together with a reader, hoping to win that person to your political side, it’s a lot like explaining why your product is superior, in hopes that a sale will result, or like trying to talk someone into an overnight visit, in hope that, well, you know. Persuasive rhetoric is what it’s all about. The ancient Greeks and Romans knew a thing or two about planting ideas in other people’s heads, and throughout the ages, some principles have remained constant.

In 1998, a very present-adaptable “how-to” piece was published (and can be downloaded.) At the time, the author’s bio read like this:

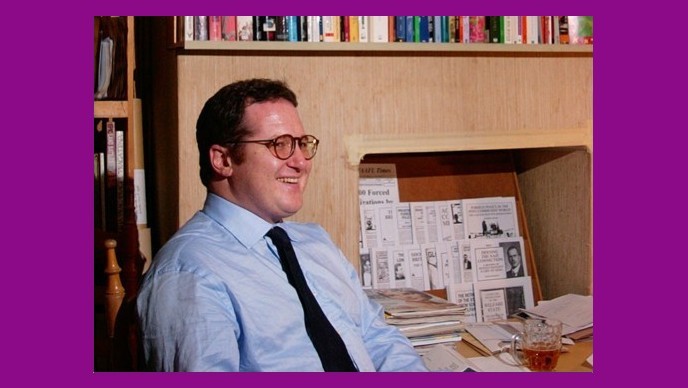

David Botsford is a freelance writer and therapist. He has written extensively for the Libertarian Alliance on a wide range of subjects including the cinema, education, gun control, and the case against Britain being part of the Europe Union.

It’s called “Thirty Six Pieces of Advice about How to be a Libertarian (and Libertarian Alliance) Writer.” Not 10, not 24, but an entire 36, and well worth the attention of an aspiring persuader. Of course, from any such list, whether prescriptive or proscriptive, we are free to pick and choose. Buried treasure lies within.

Botsford expands wonderfully on all of these suggestions, so please go read him. This is mostly a list, with quotations from him, or comments that might be applicable to newsbloggers and the like. The spelling has been Americanized. Here we go.

1. Read Orwell on the English language.

2. Write what you know about. (He mainly means, don’t write what you don’t know about.)

3. Include “pictures and conversations.” (In 1998, this wasn’t so easy, but now pictures and conversations are everywhere. Can there be too much of a good thing?)

4. Use recognized authorities as far as possible.

5. Link your ideas with the real world. (Botsford goes on to say, and this is something that will never change:)

Many people find questions of abstract philosophy incomprehensible or irrelevant, so cite specific examples in the real world to make your point plausible.

6. If possible, take the discussion away from politics and economics.

Show how people are actually going to be demonstrably better off in every respect — and how they might do things in very different ways — as they gain greater and greater freedom.

7. Read good writers who wear their scholarship lightly. (He cites, among others, Bertrand Russell and P.J. O’Rourke.)

8. Everybody has the right to have their ideas examined one at a time.

Accept that individuals often have a variety of views to put forward, each of which must be accepted or rejected on its merits.

9. As far as possible, discuss subjects that haven’t been covered in detail. Avoid the old chestnuts.

10. Don’t just sloganize — explain in detail.

11. In defense of Mr. Gradgrind. (A Dickens character, explained in detail. The point is:)

Give the reader as many incontrovertible facts as it takes to make your case — and keep any speculations down to the bare minimum. Also, check your facts thoroughly against reputable sources of information. If a reader notices even a trivial factual error in your writing, he or she will naturally doubt the accuracy of everything else in the piece.

12. Read important writers in the original. (This is about the necessity for in-depth research, if the persuasive writer is at all serious about wanting to be believed.)

13. Read and quote from the opposition.

14. Speak softly — but carry a big stick.

Your tone in writing should be moderate. Avoid the gratuitous abuse of people, the use of hysterical language, or over-stating your case; allow the reader to experience anger or enthusiasm because of the facts, analysis and arguments they read, rather than the tone in which it is written.

15. Avoid negatives — state positively. (And stress the benefits!)

16. Never underestimate what freedom and the market can achieve.

17. Don’t assume that the reader necessarily knows much about the subject.

18. Find something to “hang” your argument on, such as a current event, a television program, a politician’s speech, a book, an article or a film… It will make your writing relevant, show that you are keeping track of current developments, and be a useful “frame” for your article. (There has been perhaps a little too much of this, also, since the advent of the Interwebs. It’s the nature of the beast. Keywords are king.)

19. Humor is permitted — but let it come out of the subject rather than forcing it.

20. Read about your subject — preferably the most recent research by the most respected authorities, and those who have actively participated in what they are describing.

21. Avoid false over-generalizations… Give credit where it’s due.

22. Be sympathetic to the aspirations of the common people.

23. Recognize difficulties and problems with libertarianism. (Or your product, or the sleepover idea.)

24. Avoid taking too many examples from the United States. (Or your country of origin. Botsford is talking about libertarian arguments here, but it really does apply across the board. It’s a big world out there, where a lot of stuff happens in all different kinds of fields — stuff worth knowing about.)

25. Don’t automatically repeat widely-held myths.

26. Every article should make one specific point.

27. Avoid comparing your opponents with the German Nazis, except where very strictly relevant. (With apologies to Botsford, he should have saved this one for last, for comedic effect. Because, 15 years later, it is still so true.)

28. Don’t look on all writing as necessarily a “win-lose” situation.

29. Don’t assume that libertarianism is a hated philosophy.

30. Write about people. Make issues into one individual’s story. (Again, this is one of the areas in which online communication shines. Charles Ramsey!)

31. Avoid sectarianism.

32. Write of the relevance to libertarianism of your interests other than politics and economics.

33. Avoid parish-pump politics. Most people are not very interested in hearing the details about disputes between Ayn Rand and Nathaniel Branden in the 1960s, or between David Kelley and Leonard Peikoff in the 1990s. (Then again, some are fascinated. It all depends.)

34. Challenge generally accepted ideas about what is and is not on the side of “freedom.” (Or your product, or the sleepover idea.)

35. Read Micklethwait on footnotes. (Brian Micklethwait was Botsford’s editor. ‘Nuff said.)

36. Reduce Brian’s workload.

Check your writing thoroughly for misspellings and misprints before you send it in. Use your word processor’s spell-checker, and then check the printed paper for errors, including proper names, which can be checked in reference books… If people spot typos, they often assume that the writing itself is inferior.

So there you have it. Now, get to work.

Image of David Botsford by Brian Micklethwait.