Pretend you’re a print-oriented person who just read a serious article, a New York Times op-ed, no less. “The Slow Death of the American Author” was written by Scott Turow — attorney, Authors Guild president, and himself a bestselling author who champions the rights of the multitudes of authors who do not attain bestseller status. His perceptions carry some weight, and one of them is that “the global electronic marketplace is rapidly depleting authors’ income streams.”

Pretend you’re a print-oriented person who just read a serious article, a New York Times op-ed, no less. “The Slow Death of the American Author” was written by Scott Turow — attorney, Authors Guild president, and himself a bestselling author who champions the rights of the multitudes of authors who do not attain bestseller status. His perceptions carry some weight, and one of them is that “the global electronic marketplace is rapidly depleting authors’ income streams.”

The lugubrious title might be all too prescient. A few of Turow’s points are:

- There are many e-books on which authors and publishers, big and small, earn nothing at all. Numerous pirate sites, supported by advertising or subscription fees, have grown up offshore, offering new and old e-books free.

- Search engines […] point users to these rogue sites with no fear of legal consequence, thanks to a provision inserted into the 1998 copyright laws. A search for ‘Scott Turow free e-books’ brought up 10 pirate sites out of the first 10 results on Yahoo, 8 of 8 on Bing and 6 of 10 on Google, with paid ads decorating the margins of all three pages.

- Google […] partnered with five major libraries to scan and digitize millions of in-copyright books, without permission from authors… Google says this is a ‘fair use’ of the works, an exception to copyright, because it shows only snippets of the books in response to each search.

Turow doesn’t buy that snippets rationale, not for a minute. For although it is chopped into little bits, the entire book is, ultimately, available. Furthermore, each fragment of it provides Google with the armature for an array of advertisements, none of which benefit the author or even the publisher of the original book — not one little bit. His crowning argument is strong:

If I stood on a corner telling people who asked where they could buy stolen goods and collected a small fee for it, I’d be on my way to jail. And yet even while search engines sail under mottos like ‘Don’t be evil,’ they do the same thing.

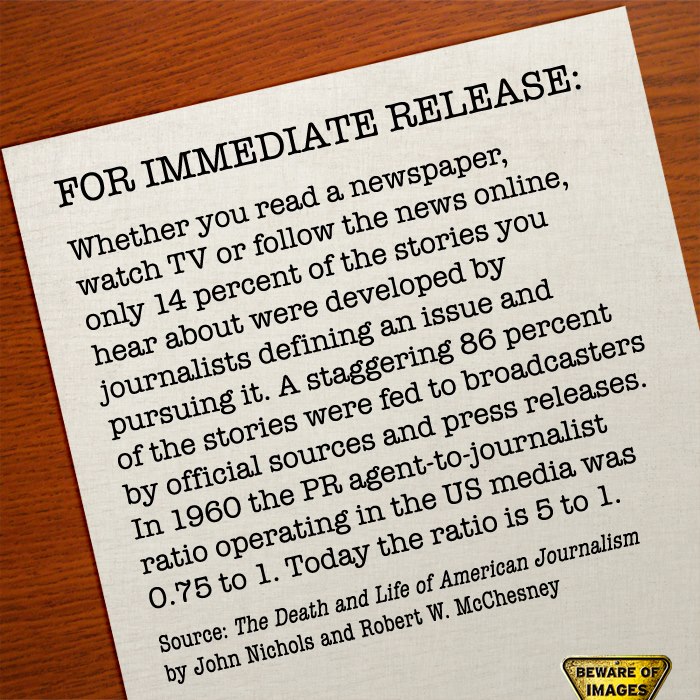

Next, imagine you’re blasting through a stream of Facebook flotsam, and are stopped short by the graphic shown on this page, which gets your attention because its angular presentation makes the whole page look skewed. It includes some alarming allegations:

Whether you read a newspaper, watch TV, or follow the news online, only 14 percent of the stories you hear about were developed by journalists defining an issue and pursuing it. A staggering 86 percent of the stories were fed to broadcasters by official sources and press releases. In 1960 the PR agent-to-journalist ratio operating in the US media was 0.75 to 1. Today the ratio is 5 to 1.

This won’t be a rant about the egregious misuse of a perfectly good word to describe quotations, observations, or rude comments attached to pictures and launched into cyberspace. These things are called “memes” and there is no changing it. Suffice it to say, a meme can make any claim, and can be a fount of astonishing misinformation. Naturally, you want to know where this stuff came from, and the source is obligingly given: The Death and Life of American Journalism, by John Nichols and Robert W. McChesney.

Hmmm. This could lead to some very interesting reading, and maybe even the desire to quote other parts of the source material. Which means you want the body of the text, so a search for “pursuing it. A staggering” seems like a good bet. And it leads to, predictably, books.google.com, where you learn that these paragraphs are actually from the preface to the paperback edition of the McChesney and Nichols work.

But the search also offers a more aesthetically pleasing and, importantly, copy-and-pasteable version, on a Tumblr page mysteriously titled 08-23-47 whose self-description says:

We see the racial, gender, class and political dimensions of personal life as fundamental to understanding contemporary circumstances. We believe in the necessity to critically examine what passes as common sense, to question what is postulated as self-evident, to dissipate what is familiar and accepted.

Sounds like nice people, but how do we know it’s okay for this copyrighted work to be hanging out on this page? One can only hope the authors put it there on purpose, because it’s a whomping big excerpt which does indeed contain passages that are both notable and quotable:

- The hallmark of great PR is that the public does not recognize it as manipulation of the facts; it is surreptitious…

- If people understand a PR campaign exists, by definition it has failed. We are supposed to think it is genuine news… As journalism declines, there will still be plenty of ‘news,’ but it will be increasingly unfiltered PR…

- Old media outlets are downsizing and abandoning journalists and new media are not even beginning to fill the void…

- This is not a crisis in which we are predicting almost unimaginable dire consequences a generation down the road unless the United States shifts course. The crisis is right here, right now…

So all you can do is hope the authors don’t mind having their ideas passed around, because if not for the tricky devices of the Interwebs, you would not have encountered those ideas in the first place. If not for that meme, in fact.

And what, you wonder, is the “Beware of Images” logo all about? As it turns out, Beware of Images is an indie film, a documentary. Its Facebook page has accumulated more than 180,000 “likes,” so what the hell, you go ahead and “like” it too. Last Friday, they posted the meme with this comment:

Today at the Conference for Media Reform, a very illuminating and insightful panel discussion with Bob McChesney, John Nichols and David Barsamian.

So, there is the connection with The Death and Life of American Journalism. Beware of Images also says:

The vast majority of online news channels are simply aggregators, they don’t do any original reporting. 90% of hard-hitting journalism was done by newspapers.

Soon there’ll be very little relevant content to aggregate.

And here’s hoping that none of this well-intentioned sharing has depleted any authors’ income streams.

Image by Beware of Images.