Even if you’ve never read his works, chances are you know the name: Salman Rushdie. Khomeini wanted him dead and issued a fatwa in 1989 calling on Muslims worldwide to put him to death, along with his publishers — all because of the novel called The Satanic Verses.

Even if you’ve never read his works, chances are you know the name: Salman Rushdie. Khomeini wanted him dead and issued a fatwa in 1989 calling on Muslims worldwide to put him to death, along with his publishers — all because of the novel called The Satanic Verses.

Now it’s years later, and the author finds himself up against the self-styled identity police of the Internet – Facebook. After dodging assassins, dealing with Facebook was easy.

You see, Facebook locked Rushdie’s account and demanded proof of identity. Hardly surprising, since Facebook and Google+ are at the forefront of the recent movement demanding real names on the Web, or natural names as they call them.

Once the required documentation was provided (“Papers, please?”), Facebook changed the name on his profile to Ahmed Rushdie, the name that appears on his passport but that he never uses. The noted author then fell into the Facebook hole that anyone needing support from it enters, an echoing chamber of no response. Not being able to get satisfaction from Facebook, he turned to Twitter.

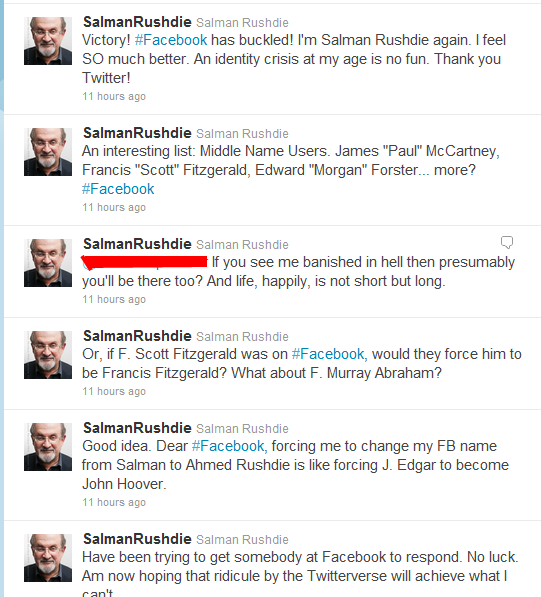

Here are Rushdie tweets over the two-hour timeframe that it took to rattle Facebook’s cage enough to get his name reinstated (they are in reverse chronological order, so start at the bottom and read them going up):

People often glibly discount the importance of the natural-name issue without really considering the implications. Rushdie’s commentary on writers’ names in the tweets above reveal only one of many issues with this stance.

Somini Sengupta notes the complex issues thrown into relief by this squabble in her Technology column for The New York Times:

The debate over identity has material consequences. Data that is tied to real people is valuable for businesses and government authorities alike. Forrester Research recently estimated that companies spent $2 billion a year for personal data, as Internet users leave what the company calls ‘an exponentially growing digital footprint.

And then there are the political consequences. Activists across the Arab world and in Britain have learned this year that social media sites can be effective in mobilizing uprisings, but using a real name on those sites can lead authorities right to an activist’s door.

‘The real risk to the world is if information technology pivots to a completely authentic identity for everyone,’ said Joichi Ito, head of the Media Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ‘In the U.S., maybe you don’t mind. If every kid in Syria, every time they used the Internet, their identity was visible, they would be dead.’

It’s a topic I’ve touched on here, on the SixEstate Blog, known in Internet circles as the “nymwars.” It also deserves the closest scrutiny and thoughtful cogitation. Widespread adoption of that policy could have a vast array of repercussions, and not just for political dissidents and writers.

To quote from the verdict from Larry Flint’s trial years ago, which I feel is pertinent here:

At the heart of the First Amendment is the recognition of the fundamental importance of the free flow of ideas and opinions on matters of public interest and concern. The freedom to speak one’s mind is not only an aspect of individual liberty — and thus a good unto itself — but also is essential to the common quest for truth and the vitality of society as a whole. We have therefore been particularly vigilant to ensure that individual expressions of ideas remain free from governmentally imposed sanctions.

In the modern age, I do not think it is out of line to say that corporate standards should be watched closely as well. The ability to assume a nome de plume is vital for uninhibited conversation, especially on those sensitive topics that require examination most.

Congratulations Mr. Rushdie! Let’s hope many more fare as well!

Source: “Rushdie Runs Afoul of Web’s Real-Name Police,” The New York Times, 11/14/11

Source: “How Salman Rushdie Used Twitter to Defeat Facebook,” Mashable, 11/14/11

Image of Salman Rushdie by Kyle Cassidy, used under its Creative Commons license.

Image: Screen capture of Salman Rushdie’s Twitter stream by Loki.