What do you do when you have a question or need to look up a word? You Google it, of course. The unsurpassable Google, along with a myriad of Internet reference sites, has been serving us well as a research tool.

What do you do when you have a question or need to look up a word? You Google it, of course. The unsurpassable Google, along with a myriad of Internet reference sites, has been serving us well as a research tool.

Some of those are better than others. Remember the now defunct Ask Jeeves, part of Ask.com, that never quite got it right? (Maybe I wasn’t asking the right questions.) Some are ubiquitous, like Wikipedia. It’s a go-to site for many, but since it’s user-generated, it isn’t entirely reliable. Some seem too specified to be rendered universally useful, but can entertain and distract all the same. A good example is NetLingo that provides Internet acronyms and text-messaging shorthand. It won’t change your life to learn that “angry garden salad” is slang for a poorly designed website, but it’s good to know (see also “cornea gumbo“).

Google rules the roost — no contest there. Not that it needs any more good PR, but there are grey semantic areas that it has helped us navigate here at SixEstate. For instance, Google has helped us set our house style guidelines with definitions that are relatively new, and/or have more than one correct spelling. When in doubt whether a word or phrase should be one word or two, should have a hyphen, or needs to be capitalized, we would Google it, and the spelling with most entries would win.

There are excellent dictionaries online as well that help with the daily copyediting efforts at SixEstate. It’s a matter of preference, but my loyalties lie with the online version of Merriam-Webster and Dictionary.com. Merriam-Webster’s window menu is divided into Dictionary/Thesaurus/Spanish-English/Medical, so you can look up a word in three different places with a possibility to also have it translated into Spanish. It also has text prediction capacity.

Dictionary.com is also part of Ask.com and is run by the InterActiveCorp (AIC) since it was bought in 2008 from Lexico, along with Thesaurus.com and Reference.com. Last year, it introduced a free iPhone app that “lets you look up definitions and synonyms from Dictionary.com and Thesaurus.com, reaching into a database of more than 275,000 definitions and 80,000 synonyms,” according to Leena Rao at TechCrunch. The app also features audio pronunciations.

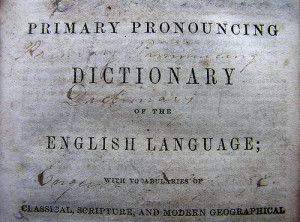

It’s not an entirely surprising sign of the times that we rely on the Internet for research and to keep us in good spelling shape. The publishers just have to adjust accordingly. For instance, the 126-year-old Oxford English Dictionary, published by Oxford University Press, may not even see its next edition printed on paper. According to Associated Press (AP) writer Sylvia Hui, the publisher had realized that so many users prefer to look up words online that the printed edition might be phased out altogether and replaced by the online version.

The numbers speak for themselves. Hui lays them out:

The digital version of the Oxford English Dictionary now gets 2 million hits a month from subscribers, who pay $295 a year for the service in the U.S. In contrast, the current printed edition — a 20-volume, 750-pound ($1,165) set published in 1989 — has sold about 30,000 sets in total.

Hui points out that the publisher has no plans to stop printing its products altogether. Schools still rely on the printed versions, she says, and non-native English speakers still buy the Advanced Learner’s Dictionary.

It’s easier for publishers to update online, though. The online edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, Hui writes, gets updated every three months; the big relaunch is currently slated for December 2010. In contrast,

By the time the lexicographers behind the century-old Oxford English Dictionary finish revising and updating its third edition — a gargantuan task that will take a decade or more — publishers doubt there will be a market for the printed form.

However, even “looking stuff up on the Web is so last year; now we have an app for that,” reminds us David Strom on the Datamation blog. Strom cites several interesting findings, which reveal that the immediacy — and not necessarily work, but play — are important to the dictionary-app users [the bullet point breakdown is ours]:

- iPhone users are more utilitarian and just want to get a word’s definition in the moment. They use them mostly during the workweek.

- Same with the Blackberry and Android app users.

- iPad users are looking for entertainment, if such a thing could be said about dictionary usage.

- They are more likely to play the audio files to hear pronunciation, getting the word of the day, and actually playing games with their dictionary apps.

- They use their app more frequently on weekends and spend about 25% more time on the app per session than the other users.

“[T]he mobile apps are getting more usage than the Web site, about two or three times more often,” Strom writes. “It seems that people want to get definitions when they are in the moment. I am sure the Dictionary.com apps have settled quite a few bar arguments.”

There is that, but let’s also express our appreciation of the savvy business sense of the people behind Dictionary.com, and hope that more online dictionaries will keep entering the smartphone app market.

Source: “Internet May Phase out Printed Oxford Dictionary,” ABC News/Money, 8/29/10

Source: “Dictionary.com Launches Free iPhone App,” TechCrunch, 05/08/10

Source: “Can an App Replace the Dictionary?,” Datamation, 05/27/10

Image by Muffet, used under its Creative Commons license.